Introduction

Speech is the most natural form of human interaction. Since the invention of computers, enabling machines to "understand" human language, interpret its meaning, and respond correctly has been an ongoing goal. Speech recognition has made this possible by acting as a machine hearing system, converting acoustic signals into corresponding text or commands.

Terminology

Speech recognition, also known as automatic speech recognition (ASR), aims to transform spoken words into computer-readable input such as keystrokes, binary encodings, or character sequences. It converts acoustic signals into text or control commands through recognition and understanding.

Interdisciplinary Nature

Speech recognition is a broad interdisciplinary field closely related to acoustics, phonetics, linguistics, information theory, pattern recognition, and neurobiology. It has gradually become a key technology in computer information processing.

Historical Development

Research on speech recognition began in the 1950s. In 1952 Bell Labs developed a system that recognized 10 isolated digits. From the 1960s, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University started work on continuous speech recognition, but progress was slow. In 1969, a Bell Labs researcher compared speech recognition to an unlikely achievement in the near term.

In the 1980s, statistical model methods represented by hidden Markov models (HMMs) came to dominate speech recognition research. HMMs model the short-term stationary properties of speech and integrate acoustic, linguistic, and syntactic knowledge into a unified framework. The SPHINX system, developed by Kai-Fu Lee at Carnegie Mellon, used the GMM-HMM framework, where Gaussian mixture models (GMMs) modeled observation likelihoods and HMMs modeled temporal structure.

In the late 1980s, artificial neural networks (ANNs), precursors to deep neural networks (DNNs), were explored for speech recognition but initially underperformed relative to GMM-HMM models. The 1990s saw increased research and industry interest due to discriminative training criteria and model adaptation methods for GMM-HMM acoustic models. The HTK toolkit released by Cambridge lowered the barrier to research.

In 2006 Hinton proposed using restricted Boltzmann machines (RBMs) to initialize deep networks, forming deep belief networks (DBNs), which mitigated training issues in deep architectures. In 2009 DBNs were applied to acoustic modeling successfully on small-vocabulary tasks. By 2011 DNNs achieved success in large-vocabulary continuous speech recognition, marking a major breakthrough and leading to DNN-based acoustic modeling replacing GMM-HMM as the mainstream approach.

Basic Principles of Speech Recognition

Speech recognition converts an input speech signal into corresponding text. A typical system comprises feature extraction, an acoustic model, a language model, a lexicon, and a decoder. Preprocessing such as filtering and framing is applied to the captured audio to extract analyzable signals. Feature extraction transforms time-domain signals into frequency-domain feature vectors for the acoustic model. The acoustic model scores each feature vector against acoustic units. The language model estimates probabilities of possible word sequences. Finally, the lexicon and decoding stage produce the most likely textual representation.

Acoustic Signal Preprocessing

Preprocessing is fundamental. During final template matching, the extracted feature parameters of input speech are compared with templates in a library. Only if preprocessing yields feature parameters that capture the essential characteristics of the speech signal will recognition be effective.

Preprocessing typically includes filtering and sampling to remove frequencies outside human speech and to suppress 50 Hz power-line interference. A band-pass filter with set cutoff frequencies is commonly used, followed by quantization. Smoothing is applied to facilitate spectrum analysis under comparable signal-to-noise ratio conditions. Framing and windowing make the signal approximately short-term stationary, commonly using pre-emphasis to emphasize high-frequency components. Endpoint detection determines the start and end of speech, usually based on short-term energy and short-term zero-crossing rate.

Acoustic Feature Extraction

After preprocessing, feature extraction is critical. Recognition directly from raw waveforms is ineffective; features extracted after frequency-domain transformation are used. Useful feature parameters should:

- Describe fundamental speech characteristics as much as possible;

- Reduce coupling between parameter components and compress data;

- Be efficient to compute so algorithms are faster and more practical.

Common features include pitch period and formant peaks. Widely used features are linear predictive cepstral coefficients (LPCC) and Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCC). LPCC is based on a source-filter vocal model and computes cepstral coefficients via linear prediction. MFCC uses an auditory-inspired filterbank and applies a discrete Fourier transform (DFT) to obtain acoustic features.

Pitch period refers to the vibration period of the vocal folds and has been important since early research. Formants are energy-concentrated regions that represent vocal tract physical characteristics and largely determine timbre. Deep learning methods have also been applied to feature extraction with promising results.

Acoustic Models

The acoustic model is a key component that distinguishes basic units. Speech recognition is essentially pattern recognition, with classification at its core.

For isolated words and small-to-medium vocabulary tasks, dynamic time warping (DTW) performs well with low computational cost. For large-vocabulary, speaker-independent recognition, performance degrades and HMM-based methods offer significant improvement. Traditional systems use continuous GMMs to model state output densities, forming the GMM-HMM architecture.

With deep learning, DNN-HMM architectures have replaced GMM-HMM in many systems, providing improved acoustic modeling.

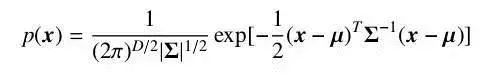

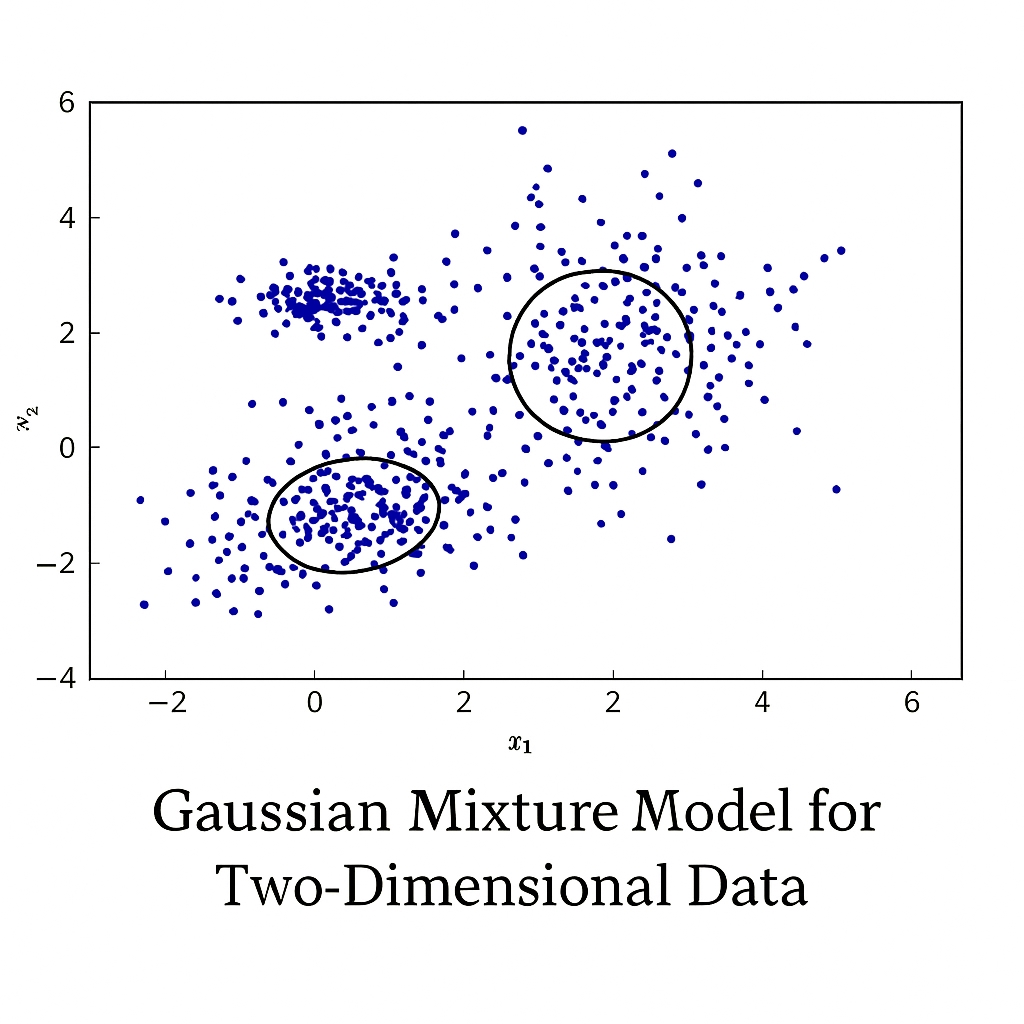

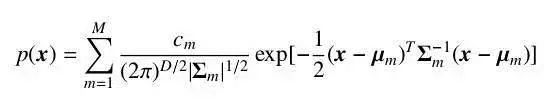

Gaussian Mixture Models

If a random vector x has a joint probability density in the Gaussian form, it is denoted x ~ N(mu, Sigma), where mu is the mean and Sigma the covariance. A single Gaussian can approximate many real-world data distributions and is computationally convenient. When data cannot be represented well by a single Gaussian, a mixture of Gaussians models the data with multiple components, each accounting for different latent sources. The resulting model is the Gaussian mixture model (GMM), widely used in acoustic modeling.

In speech recognition, feature vectors are typically high-dimensional, so the covariance matrices of mixture components are often assumed diagonal to reduce parameter count and improve computational efficiency.

GMMs offer strong modeling power: with enough components they can approximate any distribution and can be trained by the EM algorithm. Subspace GMMs and tied-parameter GMMs address computation and overfitting. Discriminative training criteria that directly relate to word or phoneme error rates can further improve performance. Before deep neural networks became common, GMMs were the default choice for modeling short-term feature vectors.

However, GMMs struggle to model data concentrated near nonlinear manifolds in feature space, which can require many Gaussian components. This limitation motivated models that can better exploit speech information for classification.

Hidden Markov Models

Consider a discrete random sequence with the Markov property: the future state depends only on the present state. If transition probabilities are time-invariant, the chain is homogeneous. If outputs are directly associated with states and observable without randomness, we have a Markov chain. Extending outputs so that each state emits observations according to a probability distribution yields a hidden Markov model (HMM), because the underlying states are not directly observable.

In speech recognition, HMMs model substate changes within a phoneme and address mapping between feature sequences and speech units.

For HMMs in speech recognition, the likelihood of a model given an audio segment must be computed. During training, the Baum-Welch algorithm, a special case of expectation-maximization (EM), is used to estimate HMM parameters by maximizing likelihood through iterative E and M steps.

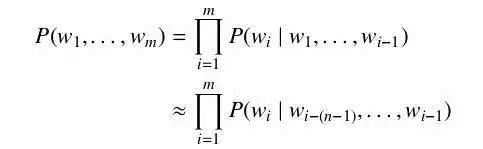

Language Models

Language models characterize patterns of human language, focusing on relationships among words in sequences. During decoding, the language model helps determine transitions between words given a pronunciation lexicon. A strong language model improves decoding efficiency and recognition accuracy. Language models can be rule-based or statistical. Statistical language models use probabilities to capture regularities and are widely used in speech recognition, machine translation, and sentiment analysis.

The most common statistical model is the N-gram language model, which assumes that the probability of the current word depends only on the previous N-1 words. The probability of a word sequence w1...wm can be approximated using N-gram probabilities. Estimation requires sufficient text data, typically by counting occurrences of history-word tuples and applying smoothing methods like Good-Turing or Kneser-Ney for unseen events.

Decoding and Lexicon

The decoder is the core component at recognition time. It decodes speech using trained models to produce the most likely word sequence or generates a recognition lattice for downstream processing. The Viterbi dynamic programming algorithm is central to decoding. Because the search space is huge, practical systems use beam search or token-passing with limited search width.

Traditional decoders dynamically construct decode graphs, which is memory efficient but can complicate integrating language and acoustic models. Modern decoders often use precompiled finite-state transducers (FSTs) for components such as the language model (G), lexicon (L), context-dependency (C), and HMM (H). These FSTs can be composed into a single transducer mapping context-dependent HMM states to words. Precompiling and optimizing FSTs increases memory usage but simplifies and speeds up decoding by allowing pruning and composition optimizations.

How Speech Recognition Works

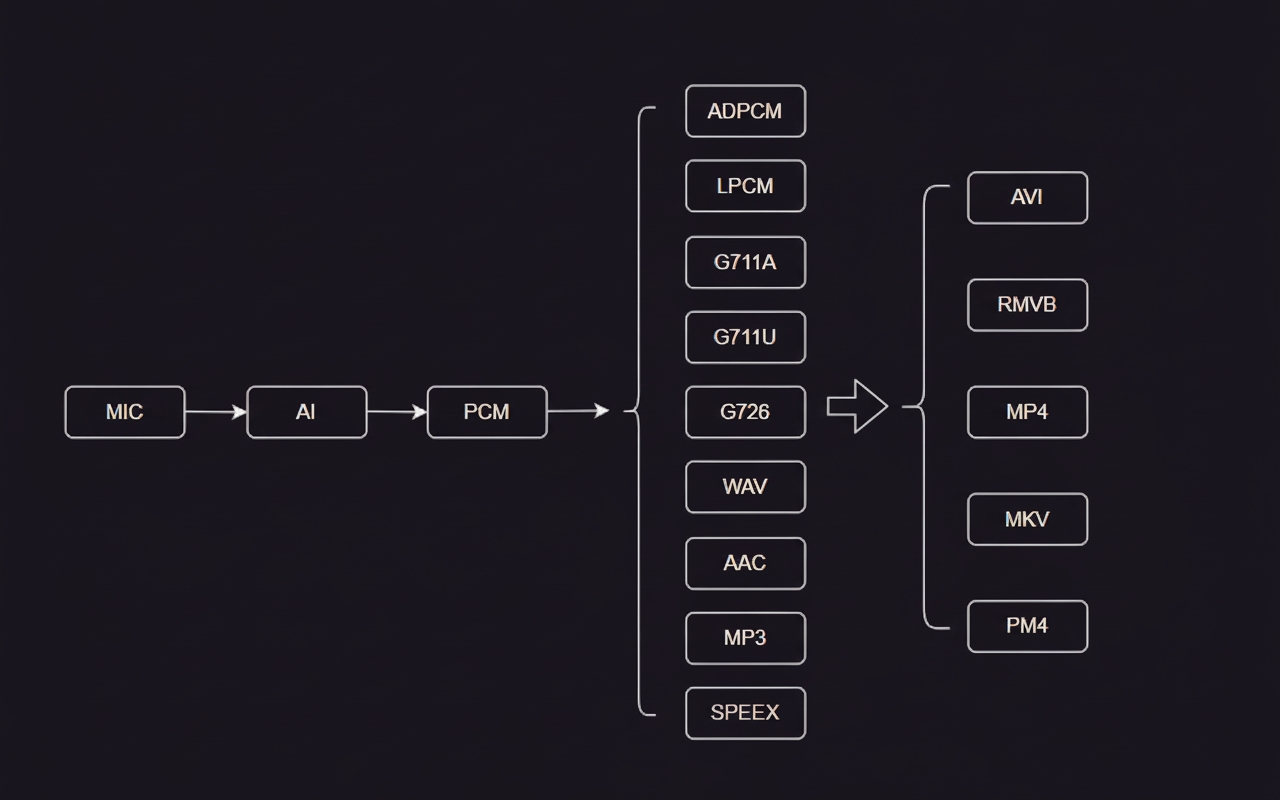

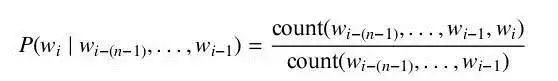

Sound is a waveform. Compressed formats like MP3 must be converted to uncompressed waveforms (for example, PCM/WAV) for processing. A WAV file stores a header and a sequence of waveform samples. The waveform is segmented into frames; for example, frames of 25 ms with 10 ms shift result in 15 ms overlap between frames.

After framing, each frame is transformed, commonly using MFCC extraction, which maps each frame to a multi-dimensional vector reflecting the content of that frame. The sequence of these vectors forms the observation sequence, an M-by-N matrix where M is feature dimension and N is frame count. Each frame is represented by a feature vector whose values can be visualized as a color map of intensities.

Key concepts:

- Phoneme: Speech is composed of phonemes. For English, a common set is the 39-phone set from Carnegie Mellon University. For Chinese, initials and finals are commonly used as phonemes, sometimes with tone distinctions.

- State: A finer-grained speech unit than a phoneme. A phoneme is often divided into three states.

The recognition process is conceptually simple:

- Map frames to states.

- Combine states into phonemes.

- Combine phonemes into words.

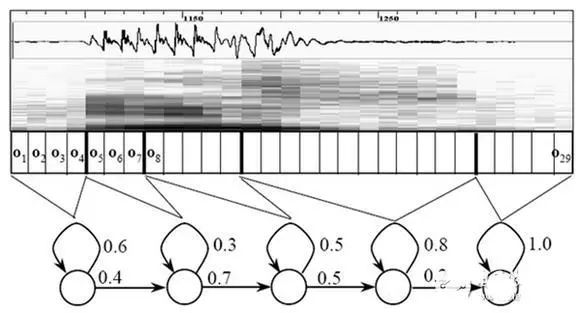

Each vertical strip in the diagram represents a frame. Several frames correspond to a state; three states form a phoneme; several phonemes form a word. If we can determine which state each frame belongs to, we can derive the recognition result.

One naive method assigns each frame to the state with the highest posterior probability for that frame. These probabilities are provided by the acoustic model, whose parameters are learned through training on large amounts of speech data. However, this per-frame greedy assignment can yield a sequence of highly varying states, producing many spurious phonemes because adjacent frames should typically share the same state for short durations.

Hidden Markov models address this by constraining possible state sequences via a state network and searching for the path that best matches the observed speech. Building a sufficiently large network enables open-vocabulary recognition, but larger networks increase difficulty in achieving high accuracy. Designing the network size and structure depends on the task.

The state network is derived by expanding word-level graphs into phoneme sequences and then into state graphs. Recognition is a search for the best path through this state network, maximizing the sequence probability, a process called decoding. The Viterbi algorithm, a dynamic programming method with pruning, finds the global optimal path.

The cumulative score for a path comprises three parts:

- Observation probability: the likelihood of each frame given each state;

- Transition probability: the probability of moving between states;

- Language probability: the probability of word sequences from the language model.

The first two probabilities come from the acoustic model, and the last comes from the language model. The language model is trained on large text corpora and exploits statistical regularities to improve accuracy. It is especially important when the state network is large; without it, decoding results tend to be chaotic.

These components make up the core of how speech recognition systems operate.

Typical Workflow

A complete speech recognition system generally follows these seven steps:

- Analyze and process the speech signal to remove redundancy.

- Extract key information and features that affect recognition and convey linguistic content.

- Identify basic units based on extracted features.

- Recognize words according to the grammar of the language and word order.

- Use contextual meaning as auxiliary information to aid recognition.

- Perform semantic analysis to segment key information, connect recognized words, and adjust sentence structure as needed.

- Analyze context to refine and correct the currently processed utterance.

Principles Summary

Three fundamental principles of speech recognition:

- Speech information is encoded by time-varying amplitude spectra.

- Acoustic signals can be represented by a discrete set of distinctive symbols independent of the speaker.

- Speech interaction is a cognitive process and must be considered together with grammar, semantics, and usage conventions.

Front-End Processing and Matching

Preprocessing includes sampling, anti-aliasing filtering, and noise mitigation due to speaker differences and environment. Endpoint detection and selection of recognition units are also handled at this stage. Repeated training may be used to reduce redundancy and form a pattern library. Pattern matching is the core of the recognition system and determines the input utterance by comparing input features with stored patterns according to defined similarity measures.

Front-end processing produces cleaned signals and extracts features robust to noise and speaker variability so that the processed signal better reflects essential speech characteristics.